“Mommy and Daddy will be right next to you,” little Sammy Fabelman is assured at the beginning of The Fabelmans, Steven Spielberg’s exploration of the creative engine that has always driven his work, his parents’ divorce. That engine is quickly given metaphorical shape in the spectacular train wreck sequence of Cecil B. DeMille’s 1952 circus movie The Greatest Show on Earth, the first film Sammy, Spielberg’s alter ego, has ever seen. The cataclysmic crash has such a terrifying and awe-inspiring effect on Sammy that he feels compelled to re-create it by becoming a filmmaker.

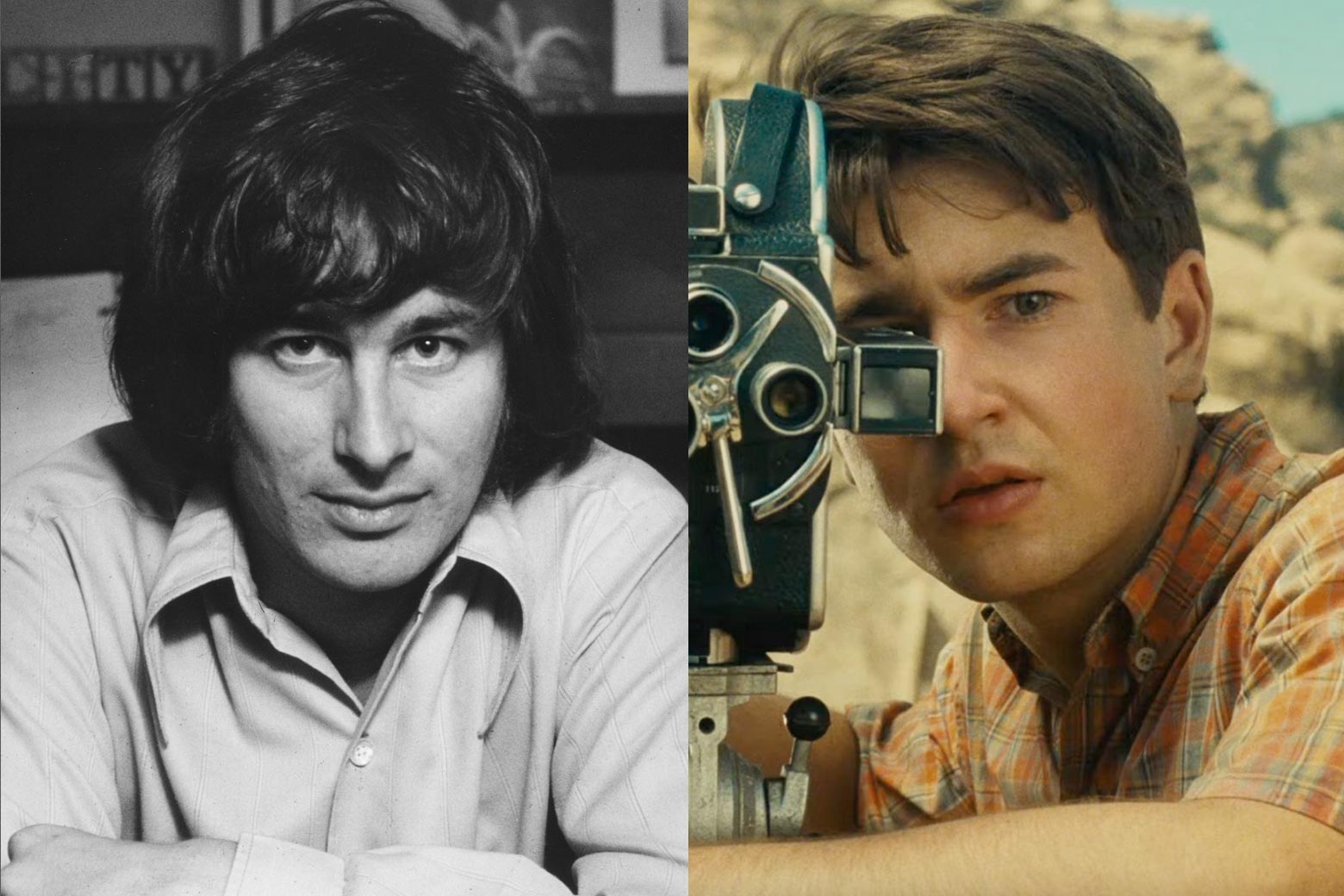

One of the principal jobs of a biographer is to distinguish the facts from the myths, rather than simply printing the legend, to borrow a phrase from The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, another formative film repeatedly quoted in The Fabelmans. When I was in the early stages of researching my unauthorized Steven Spielberg: A Biography (published in 1997 and since updated twice) and approached his office to request an interview, he declined through a spokesman, who said, “He’d be happy if there are no books” about him, but “He’s not going to stop you from writing a book.” Like The 400 Blows by François Truffaut, a Spielberg role model he directed in Close Encounters of the Third Kind, The Fabelmans is a lightly fictionalized autobiography, a version of its author’s early life with the names “changed to protect the innocent,” as Dragnet used to put it. The fictional veneer, in these cases, also allows the filmmakers to accuse some of the guilty parties who made their adolescences “hell on Earth.” That was the phrase Spielberg used to describe the year he spent at Saratoga High School in Northern California, when he suffered his most acute episodes of antisemitic bullying, painfully reenacted in the screenplay Spielberg wrote with frequent collaborator Tony Kushner.

Tilling a field that had barely been touched by other writers, since Spielberg was such a pariah among film critics and historians when I began my work, I spent three years interviewing 327 people in the five places where my subject had lived, Cincinnati, Haddon Township (New Jersey), Phoenix, Saratoga, and Los Angeles. My most important interview was with his rarely interviewed father, Arnold, a computer pioneer who provided a wealth of family history along with my saddest moment during my biographical search, when he told me, in 1996, “You know more about Steve than I do.” Steven’s mother, the irrepressible Leah Adler, was ordered not to talk to me (by whom? “The gods!” she joked), but she had been interviewed so often that I could quote her at length anyway. Spielberg’s office, as it transpired, otherwise was generous toward my research, with spokesman Marvin Levy telling people who inquired that I was “kosher.”

But even the most diligent biographical research has its limits, as I found when some of Spielberg’s most recent collaborators stonewalled me. People who knew him earlier were eager to share their stories, although I ran up against some of the mysteries in Spielberg’s life, such as his relationships with early girlfriends and the identities of the antisemitic bullies who tormented him not only in Saratoga but also, as The Fabelmans does not show, in Phoenix. Saratoga classmates mostly tried to deny that such incidents happened, but I found witnesses to back up Spielberg’s stories of the abuse he suffered there as the Jewish Spielbergs moved to progressively more WASP-y environments as Arnold’s career advanced.

With its protective coloration of semi-fictionalizing, The Fabelmans provides another layer of mythification in Spielberg’s life, or, to put it more positively, imaginative rewriting, such as with what is perhaps the subtlest dramatic scene in the film. The hulking WASP bully in Saratoga named Logan (Sam Rechner) reacts with anger when Sam Fabelman (Gabriel LaBelle) makes a movie about “Senior Ditch Day” (a facsimile of an actual Spielberg film called Senior Sneak Day, filmed on the beach in Santa Cruz). With a mixture of mischievous and unconscious retaliation, Sam’s film portrays Logan ironically as a sort of Leni Riefenstahl Nazi Übermensch. Logan is smart enough to realize he’s being mocked by the filmmaker’s slow-motion, low-angled faux-valorization, exposing him as a phony with a shiny façade. He confronts Sam, who stands up for his creative expression and Jewish pride in the face of Logan’s Aryan hostility, which turns grudgingly into respect as the bully breaks into tears, confessing his weakness. But in reality, as Spielberg once recalled, his tormentor, after seeing Senior Sneak Day, “came over a changed person. He said the movie had made him laugh and that he wished he’d gotten to know me better.”

Altering reality to heighten one’s life story, explore deeper truths, and make it come out the way one wishes it might have happened are among the purposes of autobiographical dramatization. Mostly Spielberg hews closely to the events and spirit of his youth, albeit with the compression, omission, and conflation that’s necessary even in a movie that runs 151 minutes. He has chosen to focus intensively on the primal trauma of his family’s separation, seen largely through his close relationship with his mother, here renamed Mitzi (the incandescent Michelle Williams in a richly nuanced characterization). Both Mitzi and his father, now called Burt (Paul Dano), are given scenes of mutual forgiveness with their son, in keeping with Eugene O’Neill’s belief that we must forgive our parents, and ourselves, in order to move on to full adulthood. It’s significant that the film’s title is The Fabelmans, plural.

It took Steven Spielberg a long time to forgive his father, whom he unjustly blamed for the divorce, as he discussed in a 60 Minutes interview with Lesley Stahl in 2012. Leah confessed that she had prompted the 1965–66 divorce by falling in love with Arnold’s best friend, fellow computer engineer Bernie Adler, whom she married not long after the divorce (in the film he’s called Bennie Loewy and played by Seth Rogen). Arnold told Stahl he accepted the blame within the family: “I think I was just protecting her, because I was in love with her.” The official version of the divorce had been that Arnold was a workaholic who neglected his free-spirited wife, a frustrated concert pianist, which was true enough but not the whole story. I had managed to piece together a more complete account from my sources, although I had to be somewhat circumspect about it in my book.

I also learned that Arnold had played a much greater role in his son’s life, especially his early filmmaking, than Steven had previously acknowledged. Some of Steven’s childhood friends recalled Arnold, a longtime amateur filmmaker, as seeming to be in charge of the direction of his son’s first amateur movies and as the goodhearted, brilliant fellow I was fortunate to meet. One of the members of Steven’s youthful filmmaking crew told me, “I actively liked Mr. Spielberg.” I sought with my book to encourage Steven’s reconciliation with Arnold.

Arnold seemed a more solid, well-grounded man than he appears in Dano’s charming performance as a somewhat otherworldly computer scientist. Burt has Arnold’s gentleness, but the role is somewhat diminished by Dano’s wispy and almost cartoonlike manner and appearance, the way his son still remembers him being in that period. The boy who plays the young Sammy, the ethereal Mateo Zoryon Francis-DeFord, also looks like a 3D animation figure, in his case Hergé’s Tintin, about whom Spielberg made The Adventures of Tintin in 2011. But Williams captures Leah’s exuberantly musical voice and artistic personality. She is more earthy and sensual than her husband, especially in her pivotal dance for Sammy’s camera in the woods in a translucent nightdress lit by automobile headlights. In the film’s stunning centerpiece, that camping trip, through Sammy’s filming and editing, reveals her love for Bennie, another “secret” (Spielberg’s description of this and other intimate scenes with his mother) that I had missed, unless it is a creative metaphor. Williams captures the Peter Pan–like spirit of Leah as well as her restless, pre–Feminine Mystique frustration at being miscast as a suburban housewife.

The love and energy she pours into her son’s creativity is integral to his success. But in The Fabelmans we don’t see his father playing an American soldier and mother a German soldier, each driving the family Jeep, as they did in Steven’s 1962 World War II film Escape to Nowhere, which he shows being filmed by Sammy. And Arnold collaborated with Steven and financed Firelight, his first feature film (1963–64), an ambitious project made when Spielberg was still in Arcadia High School in Phoenix and is not mentioned in The Fabelmans, perhaps because it deserves a whole movie of its own. Steven spent much of his subsequent career examining flawed father figures, but after his reconciliation with Arnold (an event so epochal it made the cover of Life magazine in 1999), he intensified his examination of flawed mother figures, as he had in earlier films such as The Sugarland Express, Close Encounters, and E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial. I found that during his year in Saratoga before his graduation in 1965 (not 1964, as the film has it—Spielberg always has trouble with dates), he actually put more of the blame for the divorce on his mother, as The Fabelmans shows in some anguished scenes.

Post-reconciliation Spielberg films such as A.I. Artificial Intelligence, Catch Me if You Can, Munich, and Lincoln give us troubled mother figures who exhibit the mesmerizing but disturbing centrifugal force Mitzi displays here. The fierce power of Spielberg’s attachment to his original shattered nuclear family will always continue to fuel him in one way or another, even if he sometimes redirects that energy onto his own large family of wife Kate Capshaw and seven children, along with his close-knit clan at Amblin and DreamWorks. “Hollywood is haimish,” declares Sammy’s Uncle Boris (Judd Hirsch), a showbiz veteran who uses the warm Yiddish word for hominess. Steven found his new home in Hollywood, where, as Mitzi puts it, he is “making a little world you can be safe and happy in,” a dreamy concept the more practical Burt cannot quite understand. He is devoted to schooling and, like other fathers of the time, including my own, can’t see movies as a serious job, only as a “hobby,” much to Sam’s dismay. (Leah similarly said in a 1963 Arizona Republic article, “We’re all for Steve’s hobby.” But she later recalled, “Our house was run like a studio. We really worked hard for him.”)

The Fabelmans movingly interweaves Sammy’s maturation through coming to terms with his parents as flawed people and the resulting effects on his early and (implicitly) later filmmaking career. And the re-creations of Sammy’s early filmmaking and exhibition demonstrate how he used those skills to win social acceptance from jocks and other classmates who scorned and abused him as a “nerd” and a Jewish outsider. That need for assimilation and acceptance also explains the Christian iconography that paradoxically permeates his work. His early experiences are the origins of his drive to be a popular artist. But as he eventually achieved more acceptance from his peers with Schindler’s List (the first movie for which he won Oscars, for Best Picture and Best Director) and other films, and became more comfortable with his Jewishness, that drive to be popular has lessened, and he has been able to pursue his more idiosyncratic creative impulses.

Some elements of his youthful development I miss in The Fabelmans include, most importantly, the school years in Phoenix and the fact that he shrewdly cast a bully in one of them as a way of controlling those who rejected him. (We see a John Wayne–like jock being coaxed into acting in Escape to Nowhere but miss the social context that preceded it.) Other events that could have been included: Steven’s embarrassment when his Orthodox grandfather Fievel Posner, wearing a yarmulke, called him “Shmuel! Shmuel!” (Steven’s Hebrew name) when he was playing football with some friends in the street and his shameful denial that the old man was his grandfather; his close but tormenting relationships with his three sisters, who are only thinly sketched in the film; Steven on his front porch in New Jersey wearing a white sheet, lit up by a revolving color wheel, as he pretended to be Jesus to offset the fact that his family did not have Christmas decorations; and his recruiting a huge but benign next-door neighbor in Saratoga (Don Shull) as a bodyguard.

And yet The Fabelmans is brimming over with exuberant life, such a richly textured and clear-minded portrayal of Spielberg’s formative family tensions that it ranks as one of the most affecting cinematic autobiographies, a worthy successor to The 400 Blows. At the end there’s an unforgettable scene of the teenaged Sam’s encounter with the legendary director John Ford, splendidly played by filmmaker David Lynch, who captures Ford’s gruffness and abrupt tenderness. As one who also encountered Ford in his office (interviewing him in 1970, on the last day of his career) and was treated in much the same way, I treasure Ford giving Sam an indelible lesson in cinematic composition before telling him, “Good luck. Now get the fuck out of my office.” Sam’s dance down a studio street in the final shot, realizing he’s been given the imprimatur of the crusty old genius, is Spielberg’s joyous and well-earned recognition that he has finally been accepted in haimish Hollywood, even if it takes a Catholic director to give him his blessing.