On October 3, renowned South Korean illustrator Kim Jung Gi passed away unexpectedly at the age of 47. He was beloved for his innovative ink-and-brushwork style of manhwa, or Korean comic-book art, and famous for captivating audiences by live-drawing huge, intricate scenes from memory.

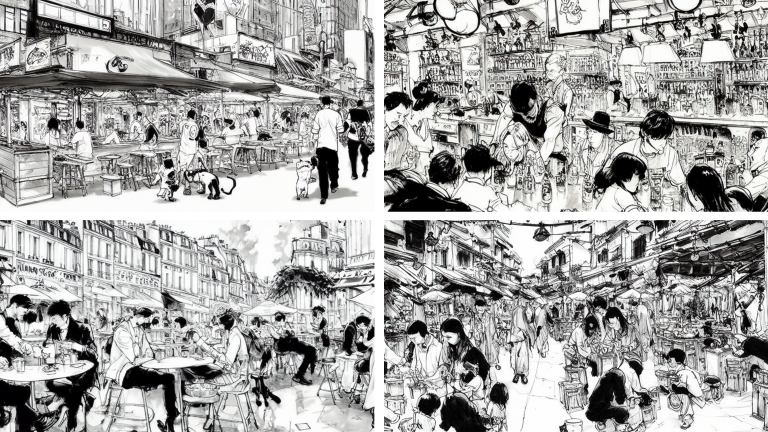

Just days afterward, a former French game developer, known online as 5you, fed Jung Gi’s work into an AI model. He shared the model on Twitter as an homage to the artist, allowing any user to create Jung Gi-style art with a simple text prompt. The artworks showed dystopian battlefields and bustling food markets — eerily accurate in style, and, apart from some telltale warping, as detailed as Jung Gi’s own creations.

The response was pure disdain. “Kim Jung Gi left us less than [a week ago] and AI bros are already ‘replicating’ his style and demanding credit. Vultures and spineless, untalented losers,” read one viral post from the comic-book writer Dave Scheidt on Twitter. “Artists are not just a ‘style.’ They’re not a product. They’re a breathing, experiencing person,” read another from cartoonist Kori Michele Handwerker.

Far from a tribute, many saw the AI generator as a theft of Jung Gi’s body of work. 5you told Rest of World that he has received death threats from Jung Gi loyalists and illustrators, and asked to be referred to by his online pseudonym for safety.

Generative AI might have been dubbed Silicon Valley’s “new craze,” but beyond the Valley, hostility and skepticism are already ramping up among an unexpected user base: anime and manga artists. In recent weeks, a series of controversies over AI-generated art — mainly in Japan, but also in South Korea — have prompted industry figures and fans to denounce the technology, along with the artists that use it.

While there’s a long-established culture of creating fan art from copyrighted manga and anime, many are drawing a line in the sand where AI creates a similar artwork. Rest of World spoke to generative AI companies, artists, and legal experts, who saw this backlash as being rooted in the intense loyalty of anime and manga circles — and, in Japan, the lenient laws on copyright and data-scraping. The rise of these models isn’t just blurring lines around ownership and liability, but already stoking panic that artists will lose their livelihoods.

“I think they fear that they’re training for something they won’t ever be able to live off because they’re going to be replaced by AI,” 5you told Rest of World.

One of the catalysts is Stable Diffusion, a competitor to the AI art model Dall-E, which hit the market on August 22. Stability AI is open-source, which means that, unlike Dall-E, engineers can train the model on any image dataset to churn out almost any style of art they desire — no beta invite or subscription needed. 5you, for instance, pulled Jung Gi’s illustrations from Google Images without permission from the artist or publishers, which he then fed into Stable Diffusion’s service.

In mid-October, Stability AI, the company behind Stable Diffusion, raised a reported $101 million dollars and earned about a $1 billion valuation. Looking for a cut of this market, AI startups are building off Stable Diffusion’s open-source code to launch more specialized and refined generators, including several primed for anime and manga art.

“I think they fear that they’re training for something they won’t ever be able to live off of because they’re going to be replaced by AI.”

Japanese AI startup Radius5 was one of the first companies to touch a nerve when, in August, it launched an art-generation beta called Mimic that targeted anime-style creators. Artists could upload their own work and customize the AI to produce images in their own illustration style; the company recruited five anime artists as test cases for the pilot.

Almost immediately, on Mimic’s launch day, Radius5 released a statement that the artists were being targeted for abuse on social media. “Please refrain from criticizing or slandering creators,” the company’s CEO, Daisuke Urushihara, implored the swarm of Twitter critics. Illustrators decried the service, saying Mimic would cheapen the art form and be used to recreate artists’ work without their permission.

And they were partly right. Just hours after the statement, Radius5 froze the beta indefinitely because users were uploading other artists’ work. Even though this violated Mimic’s terms of service, no restrictions had been built to prevent it. The phrase “AI学習禁止” (“No AI Learning”) lit up Japanese Twitter.

A similar storm gathered around storytelling AI company NovelAI, which launched an image generator on October 3; Twitter rumors rapidly circulated that it was simply ripping human-drawn illustrations from the internet. Virginia Hilton, NovelAI’s community manager, told Rest of World that she thought the outrage had to do with how accurately the AI could imitate anime styles.

“I do think that a lot of Japanese people would consider [anime] art a kind of export,” she told Rest of World. “Finding the capabilities of the [NovelAI] model, and the improvement over Stable Diffusion and Dall-E — it can be scary.” The company also had to pause the service for emergency maintenance. Its infrastructure buckled from a spike in traffic, largely from Japan and South Korea, and a hacking incident. The team published a blog post in Japanese to explain how it all works, while scrambling to hire friends to translate their Twitter and Discord posts.

The ripple effect goes on. A Japanese artist was obliged to tweet screenshots showing layers of her illustration software to counter accusations that she was secretly using AI. Two of country’s most famous VTuber bands requested that millions of social media followers stop using AI in their fan art, citing copyright concerns if their official accounts republished the work. Pixiv has announced it will be launching tags to filter out AI-generated work in its search feature and in its popularity rankings.

In effect, manga and anime are acting as an early testing ground for AI art-related ethics and copyright liability. The industry has long permitted the reproduction of copyrighted characters through doujinshi (fan-made publications), partly to stoke popularity of the original publications. Even the late Prime Minister Shinzo Abe once weighed in on the unlicensed industry, arguing it should be protected from litigation as a form of parody.

Outside of doujinshi, Japanese law is ordinarily harsh on copyright violations. Even a user who simply retweets or reposts an image that violates copyright can be subject to legal prosecution. But with art generated by AI, legal issues only arise if the output is exactly the same, or very close to, the images on which the model is trained.

“If the images generated are identical … then publishing [those images] may infringe on copyright,” Taichi Kakinuma, an AI-focused partner at the law firm Storia and a member of the economy ministry’s committee on contract guidelines for AI and data, told Rest of World. That’s a risk with Mimic, and similar generators built to imitate one artist. “Such [a result] could be generated if it is trained only with images of a particular author,” Kakinuma said.

But successful legal cases against AI firms are unlikely, said Kazuyasu Shiraishi, a partner at the Tokyo-headquartered law firm TMI Associates, to Rest of World. In 2018, the National Diet, Japan’s legislative body, amended the national copyright law to allow machine-learning models to scrape copyrighted data from the internet without permission, which offers up a liability shield for services like NovelAI.

Whether images are sold for profit or not is largely irrelevant to copyright infringement cases in the Japanese courts, said Shiraishi. But to many working artists, it’s a real fear.

Haruka Fukui, a Tokyo-based artist who creates queer romance anime and manga, admits that AI technology is on track to transform the industry for illustrators like herself, despite recent protests. “There is a concern that the demand for illustrations will decrease and requests will disappear,” she told Rest of World. “Technological advances have both the benefits of cost reduction and the fear of fewer jobs.”

Fukui has considered using AI herself as an assistive tool, but showed unease when asked if she would give her blessing to AI art generated using her work.

“I don’t intend to consider legal action for personal use,” she said. “[But] I would consider legal action if I made my opinion known on the matter, and if money is generated,” she added. “If the artist rejects it, it should stop being used.”

But the case of Kim Jung Gi shows artists may not be around to give their blessing. “You can’t express your intentions after death,” Fukui admits. “But if only you could ask for the thoughts of the family.”