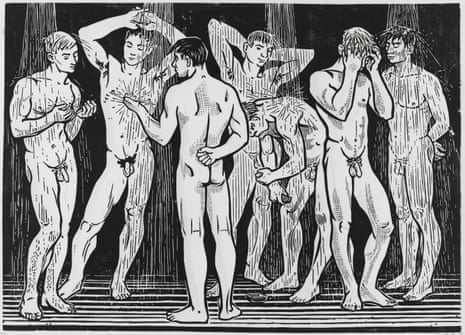

Seven men wash the sweat off their toned bodies in a communal shower. Unless you squint and mistake a tightly gripped bar of soap for something else, their limbs are suspended in tantalising proximity but never quite touch.

The German artist Jürgen Wittdorf’s 1963 linocut print, from a series titled Youth and Sport, may look like something out of a top-shelf graphic novel or the virile drawings of the gay liberation icon Tom of Finland.

Yet the sensuous shower scene was never meant to scandalise, even while the men’s yearnings were hiding in plain sight: commissioned by the East German state, a framed print hung for years in the staircase of Leipzig’s sports academy and was later reproduced in a newspaper of the regime-run socialist youth movement.

Sixty years later, it is the visible tension between outward conformity and hidden desire that is driving a revival of Wittdorf, who fell into obscurity after the collapse of the German Democratic Republic and died in poverty in Berlin four years ago. In what would have been his 90th year, a first retrospective at the Biesdorf Palace gallery has been a surprise success, drawing 13,400 visitors to Berlin’s Marzahn district since its opening at the start of September.

“What makes Wittdorf’s work so fascinating is not only his masterful craft,” said Karin Scheel, who curated the show with the gallerist Stephan Koal, “it’s also the life lived we can glimpse from these images, of a sexuality that was suppressed and later embraced.”

While the German Democratic Republic decriminalised sexual acts between men in in 1968, a year before West Germany, there were few public places where gay and lesbian lifestyles could be lived unchecked. In the early 60s there had been political campaigns against “erotic bars”, and naturism did not become a mainstream movement until the 70s.

“When it came to homosexuality, the east was as bourgeois as the west,” said Andreas Sternweiler, a friend of Wittdorf’s who curated his first solo exhibition at Berlin’s Schwules Museum in 2012.

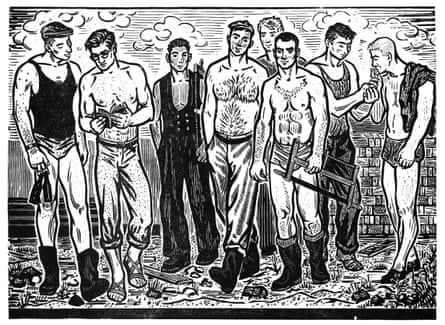

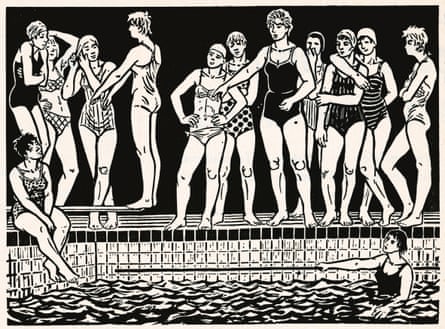

Art, however, was a place where men were allowed to celebrate male bodies, especially in a socialist realist style that fetishised a healthy physique. Wittdorf had his first sexual experiences with other men in 1963, while working on the Youth and Sport cycle, eventually coming out that year to some close friends and fellow artists. His fascination with the male form takes the viewer to groups of cyclists, Olympic swimmers or builders on a lunch break. His women are more standoffish, arms crossed over chests.

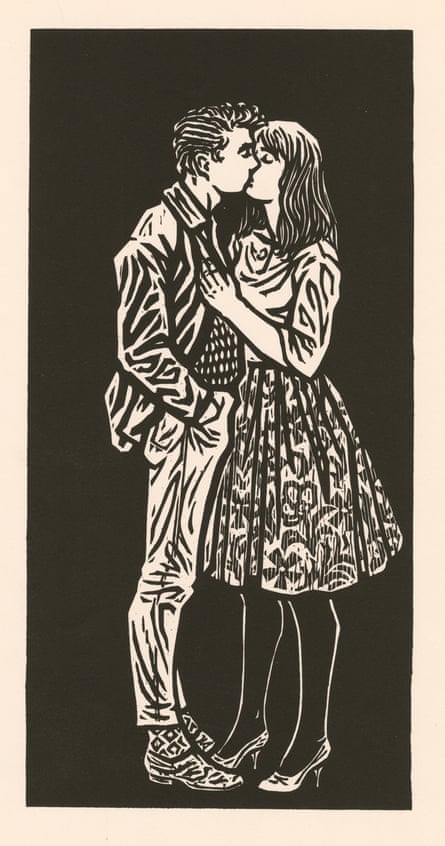

Wittdorf had won his first admirers two years previously, with a series of woodcut prints called Cycle for Youth. Young people especially could recognise themselves in his pictures of teenagers kissing in alleyways, young couples riding motorbikes, or fresh-faced fathers juggling their offspring and bags of shopping.

“He was very interested in young people’s yearning for individual expression,” said Jan Linkersdorff, a former pupil of Wittdorf’s.

“The people in these pictures are self-confident in their own right, not because of the red flags they carry or political symbols they brandish,” said Scheel of Cycle for Youth, which sold thousands of copies.

Elder East Germans in particular remained sceptical: critics found the young people in the Cycle for Youth series too westernised; newspaper readers wrote letters complaining about a picture in which a young man kept his hands in his pocket during a dreamy kiss with a petticoated woman. Sternweiler said the picture was mainly autobiographical: an early expression of his being left cold by the other sex.

While Wittdorf felt unease with East Germany’s social norms, he never openly rebelled against the system. A member of the ruling Socialist Unity party since 1957, he earned a living running drawing classes for border guards and police officers, who commissioned him to make a mural for the canteen at their Berlin headquarters. The mingling of artists and workers in creative “circles” was part of a state programme to bridge the chasm between intellectuals and the proletariat.

The Biesdorf Palace retrospective, which runs until February 2023, has portraits of punks with green hair next to men in uniform, hung in the wild floor-to-ceiling “Petersburg” picture arrangement that Wittdorf himself practised at home. A tender portrait of Lenin is, slightly awkwardly, kept apart from the rest, stuck above the elevator door.

With the collapse of the German Democratic Republic, Wittdorf’s income through teaching work ran dry. Already in his 60s, he kept running drawing classes for friends from his apartment but was eventually forced to sell off his private collection of antiques and other artists’ works in order to make ends meet.

After his death, the remaining works piled up in his Berlin apartment were sold at a house clearance auction to settle outstanding debts, with his former pupil Linkersdorff winning the bid.

Still, life outside the regulated socialist state was not only marked by disappointment. “He was embittered by his own artistic obscurity, but he also enjoyed the freedom he had gained,” said Sternweiler, whose 2012 show meant Wittdorf had a taste of his own revival in the last years of his life. “West Berlin’s gay scene was more diverse, and that’s something he cherished.”

The works from Wittdorf’s later period return to his favoured all-male lineups, with men now attired in leather chaps and straps, with neither artist or subject making any effort to hide their excitement.