In November 2017, Sharon Gayter, a 54-year-old British ultrarunner, completed ten marathons in ten days on a treadmill, with a combined time of 43 hours 51 minutes 39 seconds, breaking the former Guinness World Record by more than two hours. What’s important about Gayter’s feat now—besides being an impressive mark that still stands—is that she ran all ten marathons in the sports-sciences lab at Teesside University in Middlesbrough, England, allowing exercise physiologist Nicolas Berger to compile mountains of information. He presented these findings in a recent paper published in the International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health.

The paper’s data includes details on Gayter’s sleep, hydration, and calories burned and consumed during each 24-hour cycle; her heart rate and perceived exertion while running; and ten-day changes in her body weight, fat, and muscle. And while the data reveals interesting information about how her body responded to the challenge, Berger warns that we can’t consider her specific strategies universally applicable. “Other runners probably shouldn’t use Sharon’s example as a template for their own ultra efforts,” he says. “Sharon’s quite unique, particularly in her recovery and consistency.” Still, Gayter’s data and race experience suggest some principles runners can apply. Here are the highlights.

Slow Down to Spare Carbs

Gayter is an accomplished ultrarunner who has completed over 200 ultras, including Badwater, Marathon des Sables, and many other marquee races. Her experience was evident in the Teesside lab, as she finished all ten marathons between 4:21:21 and 4:24:38—an average of 4:23:09 per marathon. “It went exactly as I planned,” she says. “I thought there would be less than ten minutes between my fastest and slowest times.”

Gayter had hoped to consume a steady supply of fuel as she ran. According to many endurance nutritionists, marathoners should aim to consume 120 to 240 calories (or more) per hour. Gayter tried, but her stomach refused to cooperate.

“We had drinks, jelly beans, sandwiches, smoothies, and protein drinks on hand, but she became so nauseous she was unable to take them,” Berger says.

As a result, Gayter choked down a mere 180 calories on day one and just 126 calories on day two. After that she consumed only water and several handfuls of grapes during her last eight marathons—about 46 calories per marathon.

Another runner might have justifiably panicked over the low fuel supply. Gayter had been there before, however, and knew she could carry on. “I rarely take carb drinks in my ultras, due to the nausea problem,” she admits. “I thought they might be OK on this short run, but it just didn’t work out.”

Instead she ran smart, at a pace that felt sustainable. She estimates she could have run a single hard marathon in about 3 hours 30 minutes at the time—over 50 minutes faster than her average over the ten marathons. “Her marathon pace was slow, so she had little need for fast energy from carbohydrates,” Berger says. He calculates that Gayter burned fat for 67 percent of the calories she needed versus only 33 percent from carbohydrates.

“Sharon is used to running long distances with little to no carbohydrates, relying on fat stores for energy,” says Berger. “Other runners who consume as little on the run as she did would probably find their performance dropping off after three hours.”

Even with the controlled pace, Gayter’s heart rate increased by five beats per minute in the third hour of each marathon, and by another five beats in the fourth hour. Similarly, her perceived exertion rose by about 10 percent during the third and fourth hours. Berger says the increase in heart rate and perceived effort were both quite minor, and expected. “Running for three-plus hours becomes uncomfortable, and there’s not much we can do about that,” he says. “Perhaps with more energy intake and salt or electrolyte intake, Sharon would have experienced less upward drift in heart rate and effort.”

Replenish Rapidly

Berger says Gayter often tries to gain a few pounds before a big event, because she knows she’s going to lose the weight while racing. During her ten-day quest, however, she had to rely on strict post-run refueling strategies to keep up.

Immediately after finishing each marathon, Gayter turned to her replacement drink, a milk-based shake that included whey protein, colostrum powder, and a banana. “That drink was probably my most important recovery strategy,” she says. She began each day with an early-morning breakfast, and then had a snack of soup and bread an hour before running. In the evenings, she ate meat, roasted potatoes, gravy, and a medley of vegetables, followed by apple crumble with double cream. Before bed, she drank chocolate milk.

Overall, Gayter burned an average of 3,305 calories a day, including 2,030 per marathon. She was only able to consume 2,036 calories per day. This meant that she lost weight (5.7 pounds), body fat (4.2 pounds), and muscle (0.9 pounds) over the ten days.

“It’s tricky to put back what you take out in running four and a half hours a day,” says Berger. “Given that Sharon consumed so little during her runs, I think she did amazingly well.”

Cultivate Consistency and Focus

Berger credits a consistent daily structure as essential to Gayter’s success. “One thing that proved crucial is she had a daily plan, but she remained flexible as needed,” Berger says. “When you follow the same successful procedures, you can exert more control over anything that might go wrong.”

To decrease stress, each day’s marathon started purposefully late, at 11 A.M., allowing Gayter to get in optimal sleep and have time for breakfast and a pre-run snack. She slept an average of 8 hours 20 minutes per night, with the longest night’s sleep—9 hours 47 minutes—on day seven, and the shortest—6 hours 50 minutes—on day four.

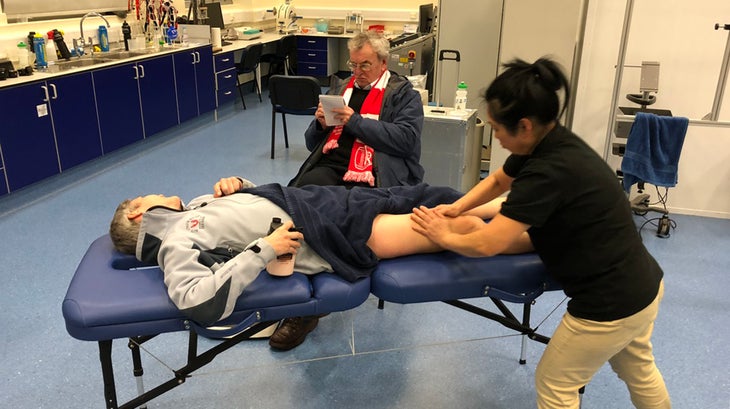

Gayter was particularly consistent in maintaining her post-marathon recovery plan over the ten days. “She was sipping her recovery drink even as I was doing the post-run tests, and then she had a massage,” says Berger.

She also didn’t try to distract herself from the long daily efforts. During her almost 44 hours of treadmill running, she didn’t need to watch TV or listen to music or audiobooks. “I am mentally strong, and I can focus on the job at hand,” she says. “Music and people talking to me are a distraction. My mind works in numbers. I focused mainly on my pace and milestones, like every kilometer or ten kilometers.”

How many more days could Gayter have continued running marathons at the same pace? That’s impossible to say, but both she and Berger made the same estimate—five more days. “I didn’t want to go any faster, because I would have risked more nausea and perhaps have missed the record,” she says. “But I had plenty in reserve.”