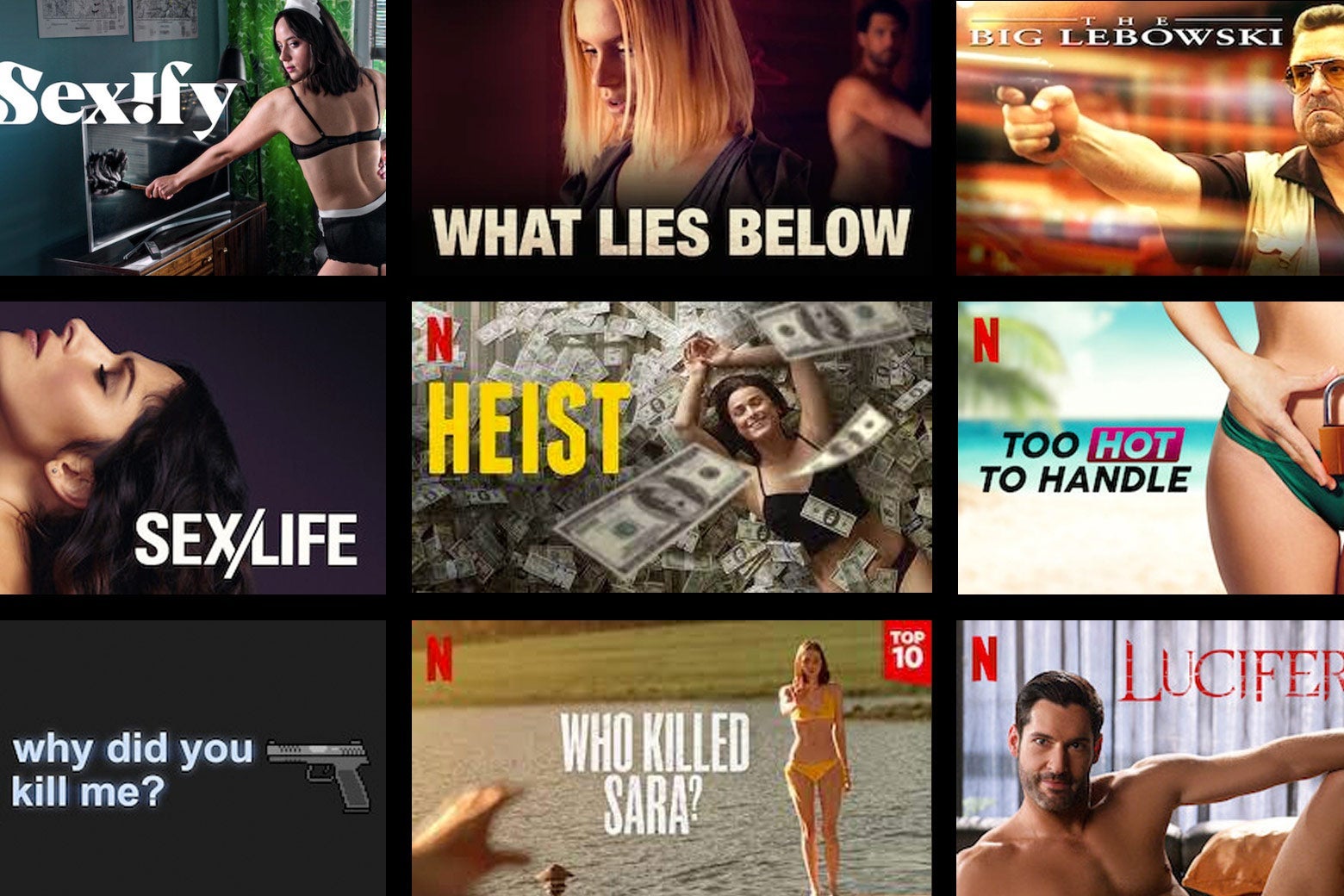

I’m on my couch, scrolling, scrolling, scrolling. As I scan my Netflix page, which rectangular tiles leap to the forefront of my attention? Well, there’s What Lies Below, with its promotional photo of an impossibly hunky man emerging, dripping, from the surface of a lake. There’s Sexify, with its promotional photo of a woman’s face seemingly captured at the peak of passion. Or maybe I should watch Lucifer, its star staring shirtlessly into my soul, his chest so uncannily hairless it looks like a video game character’s.

The answer to What Lies Below might be a jacked aquatic geneticist with a Superman jaw line, but other mysteries are left teasingly unsolved by Netflix’s most popular titles. For a while this spring, Why Did You Kill Me? jostled for space on the Top 10 list with Who Killed Sara? Why did you kill me? Who did kill Sara? Is it the girl in the yellow bikini? Or is she Sara? There’s only one way to find out: click.

In these late-pandemic days, there’s a woozy familiarity to the screen where we make most of our entertainment decisions. To anyone who’s ever written headlines for online media, Netflix looks familiar. As competitors begin to nip at the streaming giant’s heels, Netflix seems to be flirting with the tantalizing tools that web editors discovered a decade ago or more: the curiosity gap, the sexy thumbnail, the misleading image. A homepage is a homepage, after all, and these days, Netflix has discovered clickbait.

Netflix has always been devoted to getting users to click on a show—and fast. The network’s own research shows that users consider each title for a whopping 1.8 seconds, and that if users don’t find anything in a minute and a half, they’re gone. In the battle against “analysis paralysis,” the network is constantly experimenting with new ways to make items on the homepage as appealing as possible.

And Netflix recognizes that artwork—the thumbnails they present—is crucial to that decision-making. Since 2017, Netflix has customized its tiles based on a user’s viewing history, a change from its original quest to find the One Thumbnail to Lure Them All. This means (to take Netflix’s example) that if you watch a lot of romance, the company might serve you a thumbnail for Good Will Hunting that features Matt Damon and Minnie Driver smooching. If you love comedy, your Good Will Hunting thumbnail might feature Robin Williams. (More questionably, as outlets such as Wired have reported, if you’re Black, you’re going to end up seeing Black performers in your thumbnails, even if they’re relatively minor characters in the movie or show. I see Liam Neeson in my Love, Actually thumbnail; others might see Chiwetel Ejiofor.)

The service’s homepage, and the shows the network acquires, has long been ruthlessly optimized to appeal to very specific audiences. When new content springs up on your Netflix homepage, it is often brazenly similar-but-not-quite-related to content you’ve enjoyed before. Following the success of the comically generically titled Money Heist, Netflix recently debuted the new, even more generically titled hit Heist—one thumbnail featuring, just to leave no stone unturned, a woman wearing only her underwear and a cascade of $20 bills.

Sometimes the service stretches so far that it seems to verge on out-and-out misdirection: Take Ragnarok, a Netflix title illustrated by an image of Thor’s mighty hammer. Click for this new Marvel Comics Universe series, and you’ll wind up watching a perfectly pleasant Norwegian show about Norse mythology. And the company’s dependence on personalized artwork means it often seems to be playing 4-dimensional chess with recommendations. For some reason—maybe the action movies I recently streamed?—my homepage illustrates The Big Lebowski with a photo of an angry John Goodman pointing a gun, as if the Coen brothers’ comedy is actually some kind of revenge thriller.

I mean, whatever. As long as there have been movies, there have been marketers scheming to get people to watch them. But this spring and summer, things have looked a little different over at Netflix. The company seems more brazen in its strategies, more willing to promise something and then absolutely fail to deliver, often using headline tricks familiar from the social web. That’s what clickbait is: luring someone into clicking, and then delivering something other than what the headline made them want. You ask a question, but you don’t answer it. You promise satisfaction, but you leave the user unsatisfied.

You might lazily click on a thumbnail for Sex/Life—featuring its beautiful central character gasping sweatily—not because you expect quality, exactly, but because you hope for a certain kind of breezy trash: Skinemax for the 21st century, with just a little bit of character development to help it go down easy. It might not even matter if it isn’t good. It just needs to satisfy the urge you felt when you clicked on it.

But many of Netflix’s recent clickbait hits aren’t following through on their promises, implicit or explicit. Sex/Life is “more soapy than sleazy,” as Slate’s Karen Han put it, larding its episodes with vanilla sex scenes but making that hot main character’s moral dilemmas so dull that the scenes are impossible to enjoy. What Lies Below offers neither great sea-monster sex nor actual thrills. Cripes, you can keep clicking through an entire season of Who Killed Sara?, 400 minutes of melodrama, only to … never find out who killed Sara! Tune in for Season 2, I guess.

Living through the past decade in online news has made me a little suspicious of this particular kind of all-hat-and-no-cattle marketing. Take those titles-in-the-form-of-questions, for example. In their bluntness they beg an answer, and call to mind the “curiosity gap” headlines that took over media in the mid 2010s, as every website tried to replicate the success of Upworthy: Someone Killed Sara. You’ll Never Believe Who It Was. Similarly, the blandly sexy thumbnail images are reminiscent of the most basic of chumboxes, those occasionally disturbing programmatic ads that take over the bottom of websites (including, at times, Slate) that need to scrape a little more revenue from their online real estate.

It seems unlikely that Netflix’s trend toward clickbait in 2021 reflects some executive decision; it’s probably a confluence of a few surprise hit titles and a machine-learning algorithm that’s just figuring out this particular flavor of human gullibility. Because clickbait works—at least when users first encounter it. It worked when Upworthy and other sites started playing with it in the early 2010s, and the presence of these titles all over the network’s “hundred percent objective” popularity lists suggests they are working now. And once an algorithm sees something working, it’s going hell-for-leather to replicate those results as much as possible.

The question is: What will Netflix do about its algorithms discovering humans’ basest instincts? There’s evidence that even now, their internal metrics are shifting to emphasize not whether you click on a show but whether you stick with it. As of 2019, Netflix’s definition of whether a show had been “watched” was simply that a viewer had seen two minutes of it. That’s an obviously bad metric; two minutes isn’t even enough time to figure out that Chris Hemsworth isn’t in Ragnarok! But I spoke to several people familiar with the metrics Netflix uses internally and shares with creators, and they suggested that stickiness—whether viewers make it 80 percent of the way through a series, for example—is increasingly becoming more important than whether viewers click in the first place. “Things at Netflix change constantly,” one show creator told me, and “we don’t get a lot of information,” but it was made clear to this creator that their show was renewed not because of huge numbers of people clicking but because a high percentage of people watched the whole season.

And that’s good! This is the kind of policy that will, hopefully, nip Netflix’s clickbait bloom in the bud. Take it from me, on behalf of online media: It feels great at first to get people to click on girls in bikinis asking provocative questions, but you’ll never guess what happens next.