The Olympics are going on a diet. After decades of host cities stuffing themselves with expensive, useless velodromes and riflery ranges, the International Olympic Committee has relaxed its requirements—not out of magnanimity, mind you, but because cities stopped bidding. The new emphasis is on temporary structures and adaptability, and the test case is underway in Paris, which is set to host the 2024 Games.

Instead of an isolated, ticketed Olympic Park hosting journalists, athletes, and stadiums, the Paris Games will be distributed across the city and its suburbs. Instead of a dozen brand-new stadiums, Paris is building just a handful, relying on temporary or older buildings for the rest. The most important venue, the Stade de France, will be more than 25 years old; much of the competition will unfold across ad hoc structures sprinkled through the heart of the city. Fencing in the Grand Palais, equestrian at the Chateau de Versailles, breakdancing at the Place de la Concorde (yes, there will be a gold medal for b-boys and -girls in 2024), wrestling in front of the Eiffel Tower. And an opening ceremony on the Seine. The event will be hard for Parisians to miss, for better or for worse.

And the cost? For the first time, the budget for construction (3.35 billion euros) is lower than the budget for the event itself (3.9 billion euros). That would make the 2024 Games significantly cheaper than the Games in London, Sochi, Rio, or Tokyo—the current competition, according to Japanese auditors, may wind up coming in at more than $20 billion. (Of course, there is still plenty of time to blow Paris’ budget.)

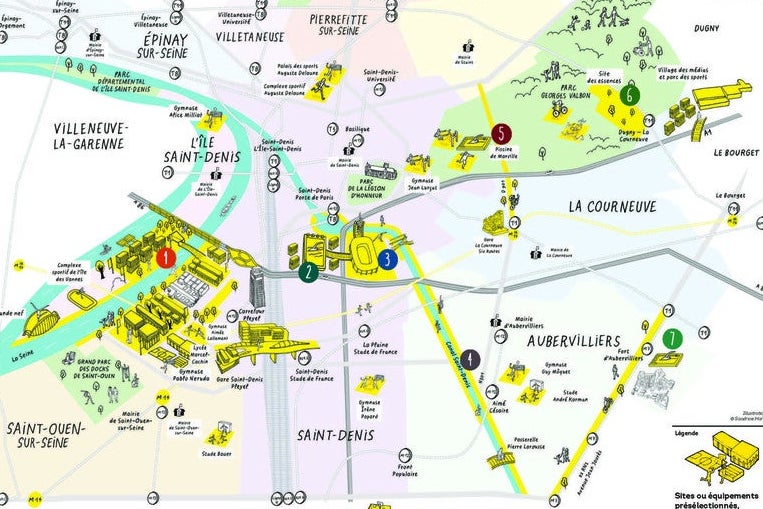

The bulk of the investment is aimed at Seine-Saint-Denis, the suburban department north and east of Paris that is the country’s poorest. Civic-minded redistribution? Easy development sites in a crowded city? Why not both? Organizers believe putting the Games’ center of gravity in the disinvested northern banlieue will not only deliver jobs, but also a sense of pride and belonging to a part of the metropolis that’s usually shunned by Parisians inside the ring road. It might just be an Olympics to feel good about. In December, a Harris poll found 84 percent of the French were in favor.

“We wanted to reinforce the ties between Paris and Seine-Saint-Denis, and make sure Seine-Saint-Denis benefits,” says Patricia Pelloux, who co-directs the urbanist think tank APUR and served on the committee to procure the Games for Paris. “It’s an area that’s had some trouble, but there’s a lot of energy there.”

The Olympic Village will be in Saint-Denis, on reclaimed industrial land along the Seine. Afterward, the dorms will be converted into nearly 3,000 apartments. Proof of concept, Pelloux says, can be found a few miles away at Clichy-Batignolles—the dream site for the Paris 2012 Olympics. London won the bid, but Paris built a huge new neighborhood on the old rail yards anyway. It’s settling in nicely.

The 2024 Olympic Village is a half-mile from the Stade de France and the new Olympic pool—the first of its size to be built in Paris since the 1924 Games, and a future community benefit. One in two sixth graders in Seine-Saint-Denis doesn’t know how to swim.

Ambre Abittan, a high school senior and avid tennis player, has lived here in Saint-Denis since she was a kid. “It’s not known as a good city,” she told me. “And the Olympic Games are going to give us a better image. You tell people you’re from here, they’re very reticent. It’s the banlieue.” That’s shorthand for hopeless housing projects and occasional riots.

In London and Rio de Janeiro, Olympic investments were criticized as a stalking horse for gentrification. That’s a long-standing worry in Seine-Saint-Denis, too. But the greater concern is that the powers that be are already cutting or delaying their most significant promises as deadlines approach and money gets tight. Volleyball got moved out of the department in December; a training pool was canceled in March.

The most disappointing news has been the delay of three promised suburban subway lines, the 15, 16, and 17, which would have come together at a new train station adjacent to the Olympic Village. Instead, one new Metro extension—the Line 14—will reach the site in time for the competition. Unlike the 15, 16, and 17, which will one day link the new hub of Olympic activity to the rest of Seine-Saint-Denis, the 14 runs straight south to the center of Paris.

Those missing connections may not matter much for athletes in the nearby dorms or spectators coming from Parisian hotels, but their absence will hurt for people in the suburbs who work or attend the Games, and belies the message on the banner outside the Olympic Village: “Saint-Denis, the Games are ours!” By mass transit, which organizers expect to deliver everyone to the competition, the Seine-Saint-Denis Olympic hub will be more accessible from central Paris than from many neighboring suburbs.

To get from the Olympic Village to a nearby Olympic training pool being constructed a couple miles to the east in Aubervilliers, for example, would have been two stops on the Line 15. Instead it requires a jerky 40-minute bus ride, over the canal and under the train tracks, down narrow commercial streets lined with boulangeries, kebab shops, pharmacies, discount supermarkets, and clothing stores selling saris, waxes, and suits.

It’s proof of how modest the impact of Paris 2024 has been on Paris that, with three years to go, this training pool is about the most controversial project underway. That’s because it would displace a score of plots in the local community garden, which has provided space to plant and relax for generations of neighbors. They trundle in and out with rolling grocery bags stuffed with tomatoes and heads of lettuce. As with many community gardens, this one’s defenders argue it is a precious asset to the neighborhood—so much so that it has, for the first time, unlocked its doors to the public at large.

A band of young squatters from all around the country has set up shop here, padding barefoot over pebbles and crushed fruit to a camp nestled in the shadow of straw-and-mud barricades. The bulldozers are gathered on the other side. “Concrete’s not going to feed us,” one of the resisters says. “Less concrete, more melons!” (In French, it rhymes.) No to gentrification, no to the Olympic Games, no to the new subway line.

At the Café Casanova nearby, though, I heard a different view from Karim Ben Amira, a father of four who has lived in the neighborhood for a dozen years. “We’d like to have something for the kids,” he said of the new training pool. He’d like his kids to have a place to swim. “Look around. There’s nothing here, a café, a football pitch. It’s going to make the neighborhood lively, in spite of what’s happening to the worker gardens. You can’t satisfy everyone.”