Life

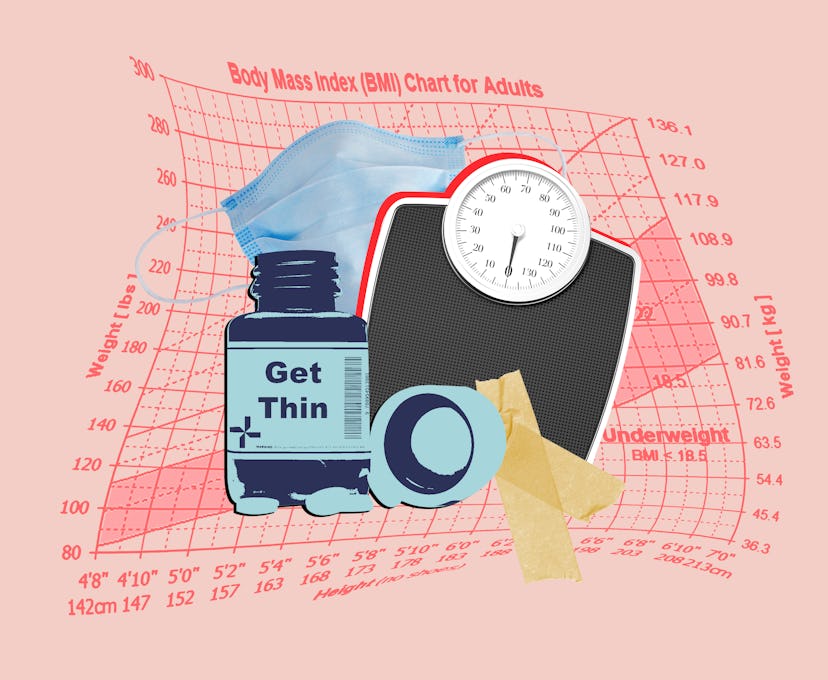

Why Do We Still Pretend Diets Work?

We survived a pandemic. Are we really doing this again?

Remember 2020, when we were sobered by our political and epidemiological reality and encouraged to practice self-care? Remember when we were asked to do literally anything that would keep us entertained in our own homes, like baking our own bread and maybe buying a nap dress?

That was early pandemic. This is late pandemic, friends. It’s May — bathing suit o’clock — and over a third of Americans are vaccinated. And you know what that means? It's time to diet, at least according to the recent media focus on pandemic weight gain. Given all we’ve been through, a post-pandemic body image whiplash this dramatic seemed unlikely. Still, Beach Body Hell: Pandemic Edition has arrived right on time. Weight loss ads are everywhere. My high school friends in diet MLMs are tearing up Instagram with exhortations to make this “the year you get healthy.” There are Noom ads on NPR and all those #pandemicweightgain TikToks. And all of it underscores how little most Americans understand about dieting, and what that lack of knowledge costs us.

This week in the New York Times, for example, the business section published what is ostensibly a story about the rebounding diet industry, which saw a sales slump last year, when we were so afraid of our bodies dying that we briefly forgot to hate them. Now that things are reopening, we're remembering.

The article perfectly captures the degree to which the diet industry has convinced even journalists and dietitians that diets lead to weight loss, and that losing weight or maintaining a low weight should be a constant priority for everyone. It discusses multiple weight loss programs without ever mentioning that diets do not lead to sustained weight loss. It declares there were healthy ways to cope with the isolation of the pandemic — "creating healthy meals or riding their Pelotons for hours" — and unhealthy ones. The description of the unhealthy ways is so cartoonish it reads like a new “woman who’s let herself go” meme: "They spent the pandemic sitting on their couches, wearing baggy sweatsuits, drinking chardonnay and munching on Cheetos." It's not explicitly gendered, but it’s hard to interpret the mention of chardonnay any other way. (“There’s no acknowledgment that some of us exercise and drink a lot of chardonnay,” was my friend Emma’s critique.)

What most people don’t know is that [diets] often lead to weight gain, and may also damage your body in profound ways.

Later on, the article does admit the ineffectiveness of dieting through the stories of people who are trying new diets because the ones they’ve done in the past always resulted in them regaining the weight. It quotes a nutritionist who says that most diets fail long-term but, "if you have a wedding to go to in two weeks, a meal-replacement program, for instance, can be helpful." The nutritionist has her own diet, which promises to “retrain your brain” to feel full on fewer calories and offers classes starting at $199. At least a third of the piece covers recent demand for Optavia, a “coaching-and-meal-replacement” program whose most popular plan costs $400 a month and is sold in part through multilevel marketing.

Everyone sort of knows that diets peter out. Eventually you stop following them, and the weight comes back. What most people don’t know is that they often lead to weight gain, and may also damage your body in profound ways. An often-cited UCLA study published in 2007 reviewed 31 long-term studies on the effectiveness of diets in the hopes of recommending that Medicare cover the most effective ones. Instead, the researchers found that almost all participants in the studies reviewed recouped the 5%-10% weight loss they had on the diet, and one- to two-thirds gained more (although researchers suspected that percentage was higher). Furthermore, the analysis indicated a link between dieting and heart disease, diabetes, and immune system changes. Read that again: That’s not a link between obesity and these various health conditions. It’s a link between dieting and poorer health. Traci Mann, now head of the Eating Lab at the University of Minnesota, led the study and said at the time, “The benefits of dieting are too small and the potential harm is too large for dieting to be recommended as a safe, effective treatment for obesity.”

Researchers haven’t reached a consensus on how dieting leads to these deleterious effects, but none of the explanations they’re looking into make dieting look any better. Does it lead to weight gain because caloric restriction causes your metabolism to change, burning less of the fuel you take in to store it for future periods of starvation? Or is it because your brain reacts to starvation with urges to binge, which then causes you to gain all of the weight back and then some? The changes in metabolic rate could change how your body processes insulin, which was one possible explanation offered for the results of a 2019 four-year cohort study of almost 4 million Americans that found weight cycling — the weight loss followed by weight gain that Mann’s team observed across diets — to be an independent risk for Type 2 diabetes. Amid ongoing panic about what obesity means for our health, we have decades of strong evidence that dieting itself is incredibly bad for our bodies, changing them on a physiological level.

One more thing: Psychologists and psychiatrists have long observed that eating disorders are almost always preceded by dieting, and not just anorexia: bulimia and binge eating disorder, as well. Cynthia Bulik, head of the Center for Excellence in Eating Disorders at the University of North Carolina, told me recently that the explanation for this could lie in epigenetics, the process by which environmental factors trigger gene expression. Bulik, who ran the 2019 study that identified eight genes linked to anorexia and is now conducting similar multinational studies to identify the genetic underpinnings of bulimia and binge eating disorder, stressed that research on the epigenetics of eating disorders is still in its infancy, but she speculated that dieting might be a trigger. “Extreme caloric restriction could activate certain genes that influence risk of developing anorexia nervosa,” she said.

Dieting ... also costs us the sense that it is OK to rest, to wear something comfortable, to eat something delicious, to watch something fun or just blissfully numbing.

People who struggle with body image often think about the consequences of their eating in terms of how much weight they will gain, and, thanks to weight stigma, how much less attractive it will make them. I don’t know any woman who hasn’t been conditioned to perform this calculation. (And not in the interest of her health, by the way. “A minute on the lips means a lifetime on the hips” is not about lowering your risk of metabolic syndrome.) But whatever your particular concern — health, weight, desirability — there is ample evidence that we should worry at least as much about the consequences of dieting.

Unfortunately, diet marketing is so ubiquitous that most people don’t know any of this, and we keep dieting, not realizing that it costs us one more thing, beyond our health, beyond the $71 billion Americans spent on diet products last year. As that Times article so starkly illustrated, it also costs us the sense that it is OK to rest, to wear something comfortable, to eat something delicious, to watch something fun or just blissfully numbing. If we didn’t live bombarded with messages that normalize dieting, we might read that article and think the subjects are acting pretty strangely for people who just survived 13 months trapped and scared in their homes. Instead of reveling in the release, making lists of what (and perhaps who) they want to do once they finally escape their own walls, they are setting weight loss goals and ordering meal replacements.

Even if you didn't know that dieting changes the way your body functions, you probably know on some level that what it asks of you, of all of us, is not just unrealistic and dreary but also distracts us from doing the things that remind us we're alive. This year of all years, why would we allow that?

This article was originally published on